![Why Some Wines Are So Damn Expensive – Breaking Down The Cost Of A Bottle Of Wine [Infographic]](http://vinepair.com/wp-content/themes/vpcontent/images/blank.gif)

It’s a common scenario: In search of a wine for dinner tonight, a red with a good-looking label and interesting description catches your eye. Let’s call it “Forlorn Hope Suspiro del Moro.” The bottle is in your hands–consumer research shows you’re 80% of the way to buying it – when the price tag catches your eye. Thirty bucks for a red from an obscure area of California?!

Most of the time, this scene ends with the unique red back on the shelf, and a more inexpensive bottle on the table, but this common experience begs a critical question: Why are some wines – especially ones you’ve never heard of – so damn expensive?

It was a chilly March morning when we drove through the Sierra Foothills and into the tiny town of Murphy’s, California to spend a day bottling wine with the man behind the Forlorn Hope label, natural winemaker Matthew Rorick. Over the course of helping Matthew bottle and pack 767 cases, we worked our way through the costs that go into those interesting $30 bottles on store shelves.

Inside an old barn we found Matthew and his helpers setting up a 50-foot metal contraption, complete with hundreds of corks, spools of stick-on labels, and one heck of a conveyor belt. At the push of a big, dangerous-looking button, the machine snapped to life. Within seconds, it was snatching up empty bottles, blasting them with gas to remove dust, then filling, corking and labeling them all in the course of 90 seconds.

Case, by case we put the freshly-filled bottles of Forlorn Hope 2014 Suspiro del Moro into clean cardboard boxes and onto wooden pallets. After the 100th case, I fell into a box-folding rhythm, and dazedly watched the bottles clink and clank through each step of the process.

First Step: The Bottles

While glass may seem like a simple cost, there’s huge variety in the bottle market – how thick is the glass? Does it have a deep or shallow indentation on the bottom? What color is it? All glass is not created equal, and that can add up to $3 to a bottle price.

Time To Fill Those Bottles With Wine

Automatic spouts filled the bottles with deep purple juice ten at a time. The provenance of the grapes has a profound effect on the cost of a bottle. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the average cost of a ton of Napa Valley grapes was $3,684 in 2013, while the cost of a ton of grapes from California’s Central Valley (where most $10 Cali Cab comes from) was a mere $340 per ton. The grapes that go into Forlorn Hope’s wines come from regions across the state, and encompass a range of grape varieties like Verdelho and Alvarelhão, which often fall in the middle of the range.

Let’s Talk About Oak

Winemaking costs come into consideration here, with the largest one being the use of oak barrels. Oak aging makes red wines smoother and rounder on the palate thanks to tiny amounts of air contact during aging, and it also adds oak flavors like vanilla and baking spices. For some wines, like red Bordeaux and Napa Cabernet Sauvignon barrel aging is essential to developing complex flavors and structure. New barrels can cost as much as $2,600 each and store about 300 bottles of wine. According to Jeanette Tan of QB Winery Solutions, an accountant for several small wineries, barrels also take up four times as much space as steel tanks holding the same amount of wine.

Using oak chips or staves–think mulch–dropped into fermenting wine is a cheaper way to add oak flavor without barrels, but the substitutes sometimes add off flavors to the juice. These methods, however, are what make the aforementioned $10 Cabernet oaky and smooth at bargain basement prices.

Seal It With A Cork

Once full, the bottles moved on to the corker. With a loud hiss, this machine punches a cork into each newly filled bottle. At Forlorn Hope, Rorick uses natural cork to seal his wines, which are more expensive than synthetic plastic cork or screw caps. Still, within the cork industry alone, variations can account for up to $3 on the bottle price if the winemaker chooses higher quality or longer corks.

Now Brand It

With a quick spin, the closed bottles are labeled and roll off the line, ready for my semi-deft hands to drop them into a box. As you may have guessed, labels get pricey too. Are they textured, or even silk-screened onto the bottles? Each step adds more to the winery’s bottom line, and the price the wine needs to command to be profitable.

Dropped into a cardboard box and onto a wooden pallet, the Suspiro del Moro was complete and ready to hit a store or bar near you for delicious consumption. But there’s a lot that happens between a noisy bottling line and the bottle in your hands, especially in regard to the price tag.

The 3-Tier System

The three-tier distribution system in the US means that before wine lands in a store near you, it needs to be bought from the winery by a distributor, who’s essentially a middleman.

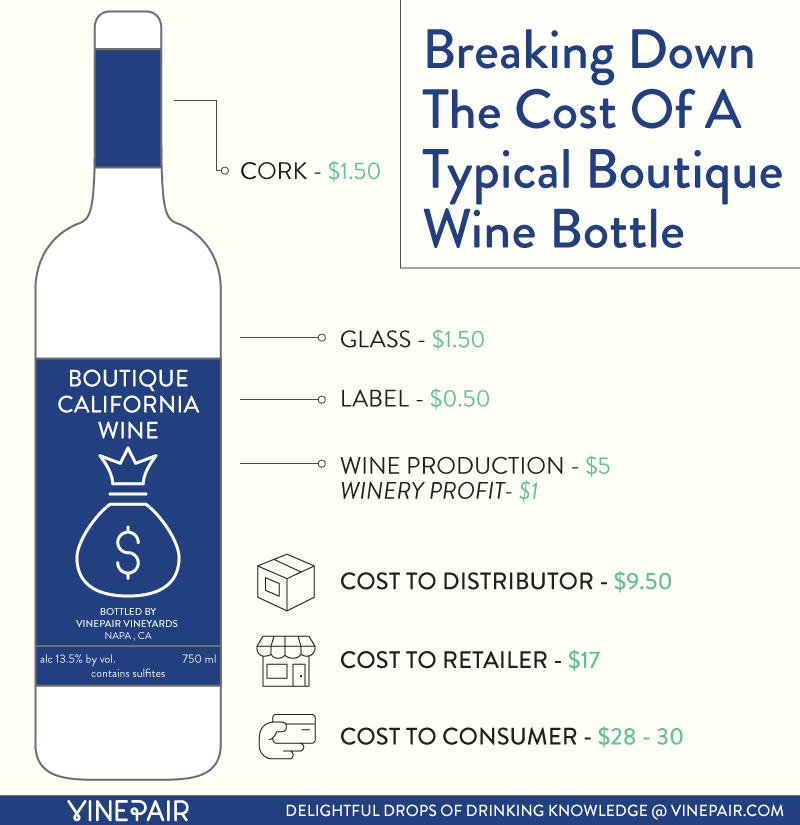

So, if that Suspiro del Moro (a yummy, fruit-laden red made from the obscure Alvarelhão grape) costs $30 on a store shelf, that means it probably cost the store owner $16, assuming a relatively standard retail markup of 45%. In turn, that means the distributor likely purchased the wine from the winery at roughly $9.50 per bottle.

Suddenly, Suspiro del Moro isn’t so expensive, and is instead confusing–especially considering that $9.50 bottle needs to be profitable and cover all sorts of winery overhead like labor, storage, and even space rental or a mortgage.

“Ultimately,” Tan points out, “The biggest cost in a bottle of wine is the cut to the middle men: the distributors and retailers. Small wineries cannot make enough volume to make a profit in this sales channel.” To reach an economy of scale, winemakers need to produces literally billions of bottles per year. In fact, 95% of wine in America is made by just 5 wineries, and 80% of America’s 8,000 wineries make only 10,000 cases per year. Tan says this difference is so huge, “It’s like they are two completely different industries.”

The massive difference in volumes explains why wines cost less at big box retailers like Costco, where wines from boutique wineries (those producing 10,000 cases) are rarely featured, since these retailers often buy wines by the truckload rather than the case. For gigantic wineries with economies of scale, fancy bottles, beautiful labels, and real corks don’t add significant costs to the wine’s final price. In short, massively produced wines are like Romaine lettuce–easy to make, quick to sell, and infinite in volume.

Wines made by small producers like Forlorn Hope are more like Kohlrabi: tough to grow, harder to sell, and rare. Rorick himself says, “The economics of small-lot winemaking at $30 and under are not very appealing from the producer side.”

If even the winemakers admit the business of making wine on a small scale is barely profitable, how do they stay in business? The secret is tasting rooms and direct-to-consumer sales from wine clubs and mailing lists–the CSAs and farmers markets of the wine biz. In these scenarios, wineries generally charge prices similar to retail, but keep all of the profits. According to Tan, that’s the difference between making a profit as a small producer or living perpetually in the red.

Walking off the bottling line, I had a good sense of the physical aspects that go into each bottle: grape juice and packaging. Add in mark ups from distributors and retailers, and there you have it–a bottle of wine for about $30.

Like shopping at Walmart instead of a famers market, every wine drinker has a choice, and most winemakers would agree that if $2 or $12 wine tastes good, then you’ve made the right choice. But sometimes, it’s worth knowing the price isn’t a fancy Napa billionaire gouging you, it’s a husband and wife team taking care of their kids, or a navy vet giving new life to forgotten vineyards.

![Why Some Wines Are So Damn Expensive – Breaking Down The Cost Of A Bottle Of Wine [Infographic] Why Some Wines Are So Damn Expensive – Breaking Down The Cost Of A Bottle Of Wine [Infographic]](https://vpstats.vinepair.com/wp-content/themes/miladys/src/assets/images/article-card-small.png)