My favorite grape-growing motto is, “If the Etruscans can do it, so can you.” In nearly every case, it’s true that grapes are extremely robust, versatile, and need hardly any attention once they’re in the ground. This writer knows first hand that you can drive over a grapevine, let deer feast on its remains, ignore it for nine months, and still find it thriving the following July.

However, there’s a monumental difference between being able to keep vines alive and being able to make fine wine from their sweet, delicate berries. In fact, there’s so much science involved in getting grapes to produce ideal berries, viticulture is a common bachelor’s degree program at universities worldwide.

Whether taking the Etruscan–try, try, try again–method or a more scientific approach to grape cultivation, certain characteristics are critical in any fine wine region. While grapes are grown and wine is made in all 50 states, not every zone has them. Before diving into specifics, let’s clarify: any ripe fruit left alone will ferment into an alcoholic beverage. Here, the focus is on fine wine production. These are wines that, while not necessarily expensive, express both varietal character (Pinot Noir-ness) and a sense of place, or terroir.

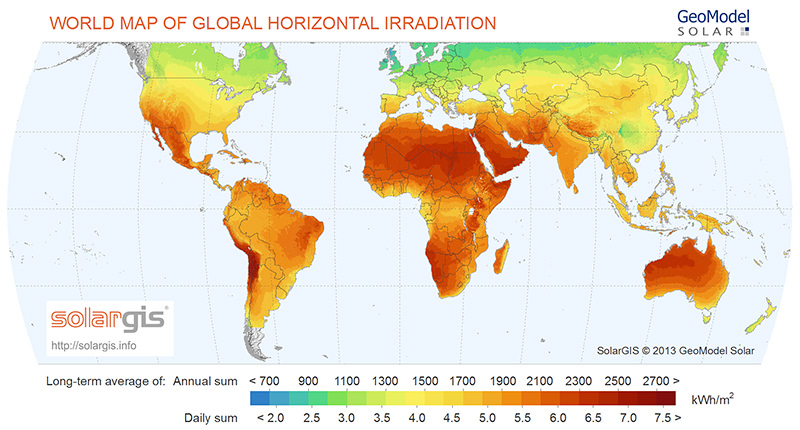

Sunshine is the first, and most important, requirement for viticulture. Sunlight powers photosynthesis, which allows the vines to grow, producing leaves and grape berries as a result. Without adequate rays and the heat that comes with them, vines will die. In general, grapes thrive between the 30th and 50th latitudes, where temperatures are warm enough for plant processes to occur. Outside of this belt, which encompasses every famous wine region in the world, winters can be too severe for vines to survive, or summers can be too hot or aren’t hot enough to support adequate ripening. A vineyard or region’s exact spot within the grape belt reflects the length of its ripening season. For example, vineyards in the northern reaches of Washington state benefit from long sunny days with cool temperatures, allowing grapes to ripen very slowly. Vineyards stretched across sun-baked swaths of Southern Spain and Portugal have shorter, hotter days where ripening happens rapidly.

In cooler areas at the edge of the grape belt, such as New York’s Finger Lakes or Germany’s chilly Mosel Valley, south-facing hillsides that maximize sun exposure are critical to grape ripening. Locales with similar temperatures, but without good exposure–like Connecticut, Poland or North Dakota–can’t make fine wines for this reason.

Adequate rainfall is another prerequisite for thriving grape vines. In many arid regions, like central California and Australia, irrigation systems compensate for water that Mother Nature doesn’t supply, and grape growing is extremely successful. However, across most of Europe–the holy grail of prosperous wine growing–irrigation is illegal. Banning irrigation is the result of stylistic winemaking laws in Europe, but also discourages grape growing in areas where wines would likely be of poor quality. On the other hand, areas that see lots of rainfall–like England and South Carolina–are prone to rot and humidity-loving fungal diseases, again making wine production extremely difficult, if not impossible.

The balance of sunshine and rainfall, which together form climates, is critical to fine wines. The unique mixes of these two elements are what make Chianti, Bordeaux, and Sonoma wines exceptional and distinctive.

Even with a seemingly ideal climate for grapes, soil composition is crucial to high quality viticulture. Unlike many crops, grapes thrive in a variety of soils, many of which are not fertile enough to support other plants. Viticulturalists look at a combination of drainage, heat retention, fertility, and minerality when examining a potential vineyard site. The round white stones that cover the ground in the Rhone village of Châteauneuf du Pape, for instance, absorb heat, protecting the vines in cool, windy nights. In addition, the rocky soil allows water to drain deep into the earth, encouraging the vines to develop a strong, downreaching root system, which prevents common diseases and death in the face of drought.

Rich, fertile soils that are heavy and compacted don’t drain well, and produce overly vigorous vines with shallow, weak root systems. Sure, these vines will deliver a massive harvest, but they’ll also be less complex and flavorful than grapes from less fertile soils.

If the goal is simply to see fermentation in action, then by all means, buy wine grape kits on Etsy for $14.95. Or make kimchi in the bathtub. But if delicious, distinctive wines are the objective, look for the Holy Trinity of sunshine, water, and soil, and enjoy every last drop.