The Willamette Valley put Oregon on the wine-drinking map. This 120-mile-long region, flanked by Portland and Eugene, is responsible for 72 percent of the state’s wine production and all of its most revered wineries. As the region’s reputation has soared, oenophiles have championed the particularities of the region as a whole, as well as the appellations within the Willamette Valley.

Though the Willamette Valley was officially established in 1983, its signature Pinot Noir grape was first planted in 1965 when several California producers, particularly David Lett of Eyrie Vineyards, traveled north in search of cooler climates. This close tie between the Willamette Valley and Pinot Noir is one of the reasons why producers see value in dissecting the appellation into more specific sub-regions. An incredibly expressive grape, Pinot Noir can demonstrate marked differences in even slightly varying terroirs, so while Willamette Pinot Noir is generally thought to strike a balance between Old World structure and New World fruit, distinct styles can differ greatly from one sub-region to another.

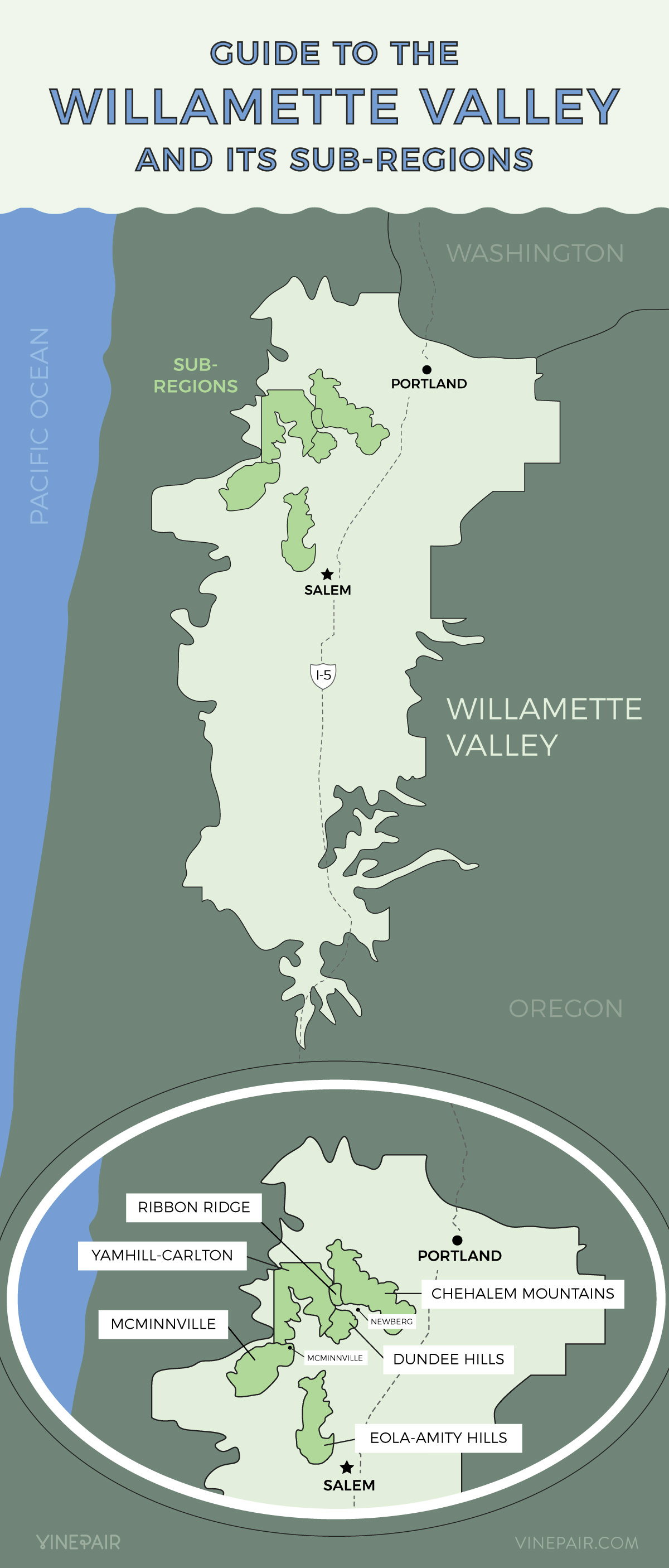

This cool, humid Oregon region has a mix of soils, including marine sedimentary soil, windblown silts, and famous volcanic basalt-based soils. These all contribute to different styles of Pinot Noir. The best of these soils are found in six distinct areas in the northern part of the Willamette Valley, particularly on the low slopes and hillsides above the valley floor, which can be too fertile for quality wine. These six regions — Chehalem Mountains, Dundee Hills, Yamhill-Carlton, Ribbon Ridge, McMinnville, and Eola-Amity Hills — gained individual AVA statuses in 2005 and 2006. They now contain over 60 percent of the Willamette Valley’s planted vineyards, cementing the area as the heart of the region’s wine production.

While more Willamette Valley Pinot Noirs are being labeled with their specific sub-appellations, the region might become even more focused in the coming years. Several petitions have been submitted or are pending final approval for new Willamette Valley appellations, such as Van Duzer Corridor, which is expected to become official later this year, and Tualatin Hills, which has at least one more year to wait before confirmation.

Until then, this guide to the Willamette Valley will take you on a journey through Oregon’s most important wine region, giving you the lowdown on exactly what to expect from each of its distinctive and delicious sub-AVAs.

Chehalem Mountains

Just 30 minutes outside Portland, the most northerly Willamette Valley appellation is defined by a series of ridges and hills that stretch from southeast to northwest. The Chehalem Mountains AVA is home to the highest point in the entire valley, and has variable soils and mesoclimates throughout. Vineyards closer to the Pacific Ocean in the northwest withstand rainier conditions, while those in the southeast tend to be warmer and drier, and grapes on higher slopes ripen earlier than those on lower slopes. These wide-ranging conditions lend themselves to high variability of the resulting wines, from light and fruity to intense and forest floor-like, all with fine structure and texture.

Dundee Hills

Home to the Willamette Valley’s first grapes, and some of Willamette’s most revered producers, Dundee Hills remains the most thickly planted area in the region. This north-south-oriented area lies west of the Willamette River and just south of the larger Chehalem Mountains area. The most distinctive component of Dundee Hills is its soil, the famous, red-hued Jory. Heavy with volcanic basalt and rich in iron and clay, the Jory provides just enough stress on vines, creating well-structured, long-lived wines. Dundee Hills Pinot Noirs tend to be concentrated and complex, the tannic structure and bright acidity built for aging, combining ripe fruit with minerality and spice.

Yamhill-Carlton

North of McMinnville, the Yamhill-Carlton AVA is centered around the two areas of Carlton and Yamhill, both surrounded by a horseshoe of low ridges. Warmth abounds and land benefits from rain protection by the Coast Range, so vineyards are spread out and interspersed with farmland, forests, and orchards. Easy-draining, ancient marine soil is present throughout, which, combined with the area’s relative warmth, creates wines with plump, plush fruit accented by sweet aromas like vanilla, tobacco, and clove.

Ribbon Ridge

Sandwiched between the previous three appellations, the small Ribbon Ridge area is technically located within Chehalem Mountains. However, it holds its own AVA designation because its distinctive soils differ from those of the variable Chehalem Mountains, comprised of deep, marine sedimentary soils like Willakenzie. Protected from the elements by the surrounding landscape, Ribbon Ridge tends to have a long, consistent growing season with relatively lower rainfall, and the Pinot Noirs here tend to be balanced between richness and acidity, combining intensity with elegance.

McMinnville

The most westerly region within the Willamette Valley, McMinnville centers around the city of the same name, one of the hubs of Willamette Valley tourism. The soil in these south- and east-facing vineyard sites is primarily marine sediment but with definite volcanic basalt as well. Rainfall is lower in McMinnville than in the easterly Willamette regions, allowing grapes to concentrate as they sit on the vines longer during the growing season. Expect McMinnville Pinot Noirs to be darkly fruited, rich, and spiced.

Eola-Amity Hills

Located south of the Willamette Valley’s other sub-appellations, Eola-Amity Hills is just west of the Willamette River. Two major influences define wines here: the shallow, basaltic soils and the cool Pacific air funneled by the Van Duzer Corridor, dropping temperatures sharply in the afternoons and evenings. This creates wines with biting acidity and delicate aromatics, making Eola-Amity Hills an ideal region for both red and white grapes. These Pinot Noirs are characterized by their nervy structure and fresh, tart fruit.