The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies in Santa Cruz, Calif., is currently conducting a study using cannabis to treat veterans suffering from PTSD. It’s reportedly the “first-ever U.S. study of smoked cannabis for a mental health condition or medical condition.”

It could lead to medication. To help people. Soldiers. Meaning legalization fear-mongers can stand down — weed and medicine are doing just fine.

If only we could say the same for booze. As psychologically flexible as we are, as wickedly nimble our marketing departments and bendable our weekend morals, civilization has yet to convincingly align booze with the pursuits of responsible medicine. But we can dream. (Frat parties would be like community health clinics! A keg stand would be as good as Downward Facing Dog! Sigh.)

Don't Miss A Drop

Get the latest in beer, wine, and cocktail culture sent straight to your inbox.In fact, we’ve tried. Basically since fermentation was discovered, we’ve sought cure-by-ABV for everything from the common cold to dyspepsia to that special category of old timey “ailments” reminiscent of Dr. Seuss (“clumsy stomach,” “knee sweats,” “pokiness of the ear”).

To celebrate millenia of our willful collective delusion, we’ve gathered some of humanity’s finest efforts. Here is a boozy history of alcohol as (almost) medicine.

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egyptians and Chinese are among the earliest adopters of booze as medicine; though in their cases, alcohol more as a vehicle for medicine, the way Red Bull is (why) a vehicle for vodka. According to Patrick McGovern, the UPenn professor who discovered basically a 9,000-year-old empty in Jiahu, China, “ancient wine and other alcoholic beverages are known to be excellent means to dissolve and administer herbal concoctions externally and internally.”

400(ish) B.C.E.

Hippocrates’ quote on wine — “An appropriate article for mankind, both for the healthy body and for the ailing man” — is so well known you can find it plastered on the kind of depressing motivational poster you’d find in a hotel conference room while getting plastered. The famous physician was an early, if unofficial, advocate of the “Wine for Wellness” movement.

400 B.C.E.

The Juang di Nei Jing Su Wen, or Su Wen, is the seminal compendium of ancient Chinese medicine. And it has the same solution for anxiety that you do, advising medicinal wine “for when the physical appearance is frequently affected by fright and fear.”

The Bible

One of the earliest practitioners of boozy medical intervention was none other than the Good Samaritan himself, who, per Luke 10:34, saw the wounded traveler and “went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine.” Timothy 5:23 advises, “Stop drinking only water and use a little wine instead, because of your stomach and your frequent ailments.” Amen.

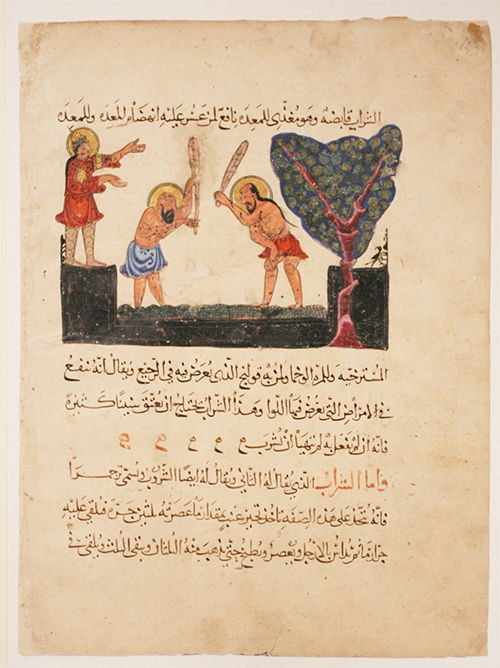

70 A.D.

Book Five of De Materia Medica , a five-volume pharmaceutical encyclopedia by a Greek physician in the Roman army, was all about wine. It was thus probably the most read, and probably the most thrown-up on. An illustration from a 1224 A.D. Arabic translation, titled “Men Treading Grapes,” notes wine is good for digestion and “for a woman with unnatural appetite.” The book also documents medical benefits of Cannabis Indica: “The herb juiced while green is good for earaches.”

1055 A.D.

In 1055, Benedictine Monks in Salerno wrote the Compendium Salernita, piously advising the use of juniper-infused wine distillate — a kind of proto-gin — for the treatment of “chest ailments.” No word on how to cure whatever hellish hangover comes from drinking too much proto-gin.

13th Century

Philosopher Roger Bacon looked like sad Santa Claus, but he was actually a brilliant polymath who made some zany predictions (flying machines?). As a booze-cure proponent, Bacon perpetuated the disastrous delusion that booze would “preserve the stomach,” but he got a little closer to the truth when he said alcohol “cheers the Heart, tinges the Countenance with red, makes the Tongue voluble, begets assurance, and promises much good and profit.” If you’ve ever been drunkenly overconfident with red cheeks and a get-rich-quick scheme, you get it.

1665

As the plague spread throughout the United Kingdom, so did unlicensed, unproven medical solutions. “Famous and Effectual Medicine to Cure the Plague,” a widely distributed print flyer, includes a number of palliatives, among them Mace Ale. It’s defined as “ale boyled with a crust of brown Bread, with one blade of Mace and two Cloves.” Taken, presumably, between bouts of shouting, “Are you kidding me right now! It’s the motherf***ing plague!”

1845

In what was either an incredibly selfless act or a tremendously successful guerrilla marketing campaign, self-taught apothecary Bernardino Branca provided Milan’s Fatabenefratellia hospital loads of his Fernet Branca as a treatment for Asiatic cholera during a particularly bad outbreak in the mid-19th century. He had no suspicion it would become a symbol of hipster drinking savvy.

Late 19th Century

When good old British imperialism found a lot of Brits transported to India, quinine rationing became necessary to prevent malaria. Quinine was potent and piquant enough that British soldiers actually used gin to cut the flavor. Thus the emergence of what’s likely the closest to a legit booze Rx you can get, the G&T. The truth is, Incans in Peru had discovered the malaria-quinine connection centuries before, using cinchona bark (the source of quinine) to cure the fever. And then, of course, good old Spanish colonialists found the cure and brought it back to Europe.

1890s

PBR plays such a huge role in the pursuit of human perfection, it’s no surprise Pabst was among the first modern alcohol brands to look for a niche in medicine. Other breweries in the 1890s were trying to market “malt extracts” — semi-nutritive, semi-sweet, semi-alcoholic — as good for digestion, convalescence, etc. So Pabst came out with a series of pamphlets with charming illustrations of the kinds of pseudo-ailments it could be used for, anything from dyspepsia to nervousness to, our personal favorite, “overworked.” (Funny how the dead look in the eyes never changes over the centuries.)

1919

Anheuser-Busch took medical malt extract to the next (obvious) level: motherhood! Its Malt Nutrine was low in alcohol, clocking in at 1.9 percent, and the company marketed it to actual babies as well as new moms. “The baby needs it in order to grow healthy and plump,” reads one line of copy. Fair enough. A 1919 Good Housekeeping ad promised mom “endurance and quick restoration and an ample supply of nourishment for the little one at her breast.”

1929

“Better than whiskey,” claims an amazing ad for something called Aspironal, an “opiate-free” (hooray!) “delightful elixir” that rings in at 10 percent ABV. “Endorsed by medical authorities to cut short a cold or cough,” Aspironal predates and utterly destroys Domino’s “30 minutes or less” policy. “If you don’t feel relief coming in two minutes,” says the Aspironal ad, “every druggist in [the] U.S.” was instructed to give you your money back. Did we mention it’s good for the whole family? “When your cold or cough is relieved,” the ad says, “take the remainder home for your wife and children.” How thoughtful!

1941

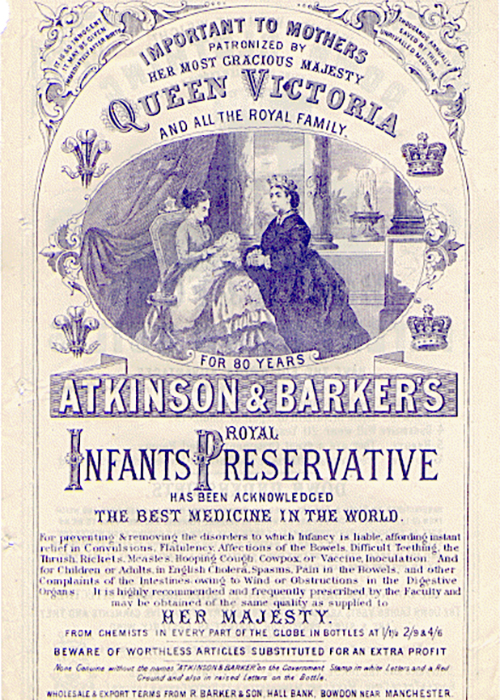

In what might be the first in a long, happy line of celebrity-booze relationships, Queen Victoria and “All the Royal Family” put their shiny, shiny stamp of approval on Atkinson & Barker’s Royal Infants Preservative, an alcoholic solution meant to fight “Convulsions, Flatulency, Afflictions of the Bowels, Difficult Teething.” Fun fact, it was also just basically a 40 percent ABV laudanum solution for babies.

1941

This was a big year for booze as medicine. Three trailblazing doctors at Cornell performed a study on themselves, drinking 95 percent ABV grain alcohol mixed with ginger ale (because let’s not get crazy) and discovered, presumably by very scientifically beating the shit out of each other, that their pain threshold was essentially doubled for two hours. The docs wisely noted it should be used to lessen the pain of cancer patients, and not “because…SCIENCE, bro!!!”

Present Day

While most of us presumably no longer have physicians prescribing us alcohol or its byproducts to cure the pains of pregnancy or common colds, there is a seemingly endless parade of studies proclaiming the health benefits of moderate consumption. A recent study shows alcohol activates a heart-healthy enzyme (move over, acai). Another suggests that alcohol can help remove toxins from your brain.

We feel better already.