Noble grape Sauvignon Blanc is an Old World enigma wrapped in a New Zealand supermarket circular. Grown and exported around the world, it’s become so ubiquitous that one Twitter user likened it to the “chicken Caesar Salad” of restaurant wine lists.

With machine harvesting and stainless-steel fermentation, the oft-imitated style is easy to make inexpensively. Aromatic and fruit-driven with crisp, mouthwatering acidity, these wines are designed to be consumed on release.

But those who feel they’ve learned all there is to know about the simple variety are in for a surprise. Some international vintners are aging Sauvignon Blanc as you might Chardonnay and Riesling. These age-worthy wines are a radical departure from the bulk bottles lining global grocery shelves and are giving the grape a new life.

Don't Miss A Drop

Get the latest in beer, wine, and cocktail culture sent straight to your inbox.Among them is Loire Valley-based ninth-generation winemaker Arnaud Saget. “We don’t think the average consumer really sees Sauvignon Blanc as a wine that can age potentially,” Saget says. “[But] that’s the philosophy of our winery.”

Saget’s family’s label, Domaine la Perriere, is currently in the process of introducing its Mégalithe Sauvignon Blanc to the U.S. market — a wine specifically designed to showcase the variety and region’s potential for aging.

“In our region, we have different types of soils and some of them will potentially give more structure to the Sauvignon Blanc and provide the grape more ability to age through time,” Saget says.

Two key factors for stabilizing white wines so they can age are high acidity and barrel fermentation and maturation. (Though not applicable in the case of Sauvignon Blanc, what’s also useful is residual sugar. That explains why some of the longest-lived whites are sweet dessert wines such as Sauternes and Tokaji.)

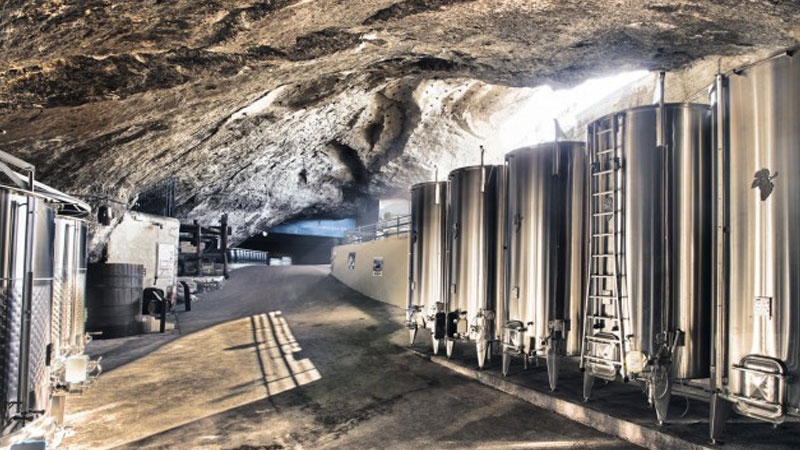

To make Mégalithe, 40 percent of the grape must stays in 300-liter new barrels for eight to nine months. During this period, the lees, or dead yeast left over from fermentation, are regularly stirred to provide “weight and complexity” to the wine. Meanwhile, the remaining 60 percent is vinified and matured in stainless-steel vats to preserve the wine’s fresh character.

Saget says wines “develop in complexity and mouthfeel” as they bottle-age, displaying pleasant truffle aromas and flinty mineral notes. Intriguingly, unlike other aged whites, Sauvignon Blanc maintains its pale color throughout aging. Ten-year-old wines are indiscernible from current vintages.

“I recently had a Pouilly Fumé which was 1985, and that was just an amazing experience,” Saget says. “It was fantastic to see how the wine was still ‘alive.’ The aromas change through time, but the wine is still there, still has acidity, and is still balanced in the mouth.”

As the Loire Valley continues to gain prominence and its wines increase in price, the prospect of selling aged Sancerre might not be as difficult as it would have been, say, 10 years ago. Sauvignon Blanc-heavy New World regions like New Zealand, on the other hand, face a much bigger challenge.

That hasn’t stopped Marlborough winery Dog Point from developing its own aged style. Operational since 2002, the producer’s critically acclaimed Section 94’ Sauvignon Blanc is noted for its ageability.

“When we commenced with the Dog Point label, one of our prime objectives was to make wines that would age respectfully,” winemaker and co-founder Ivan Sutherland writes in a recent email exchange.

Like Arnaud Saget, Sutherland believes that the key to producing age-worthy Sauvignon Blanc is “largely the influence of climate and soils,” with Marlborough’s cool climate and free-draining clay soils proving an ideal combination.

But the human factor is equally vital. Closely controlled cropping and canopy management allow Dog Point to achieve precise grape ripeness before 100 percent hand-harvesting — something that bucks the regional mechanized trend.

Section 94′ is barrel-fermented with wild yeast, where it remains for 18 months in a temperature/humidity-controlled environment. With bottle age, this style of winemaking provides stark contrast to the youthful, fresher Sauvignon Blancs.

“Aging certainly softens the wine, with less lifted aromatics and toned-down acidity,” Sutherland says. “In desirable climatic years, with controlled cropping, the wines develop a nice dried-herb, slightly honeysuckle character, with a softer, rounded palate.”

Sutherland notes that not only Dog Point, but other producers in the region are “very happy” with the results of aging Sauvignon Blanc.

With these and other examples of aged Sauvignon Blanc performing well worldwide, perhaps the question is not, “Does Sauvignon Blanc age well?” but rather, “Is there a market for it?”

Since its introduction to New Zealand in 1973, Sauvignon Blanc has put the nation on the winemaking map. It now dominates output, with more than 85 percent of New Zealand’s wine exports Sauvignon Blanc — the overwhelming majority the younger, fresher style.

Given the market for inexpensive Sauvignon Blanc, and the attractive margins it offers, it’s hard to imagine winemakers ditching this tried-and-tested style for higher-quality, ageable wines. But that doesn’t mean they don’t deserve recognition.

Thanks to the likes of Saget and Sutherland, the way we think about varieties like Sauvignon Blanc is changing. Yet there will always be a demand for good old unchallenging “Kiwi Savvy B.” That, too, is a good thing.

What ultimately makes wine more interesting than, say, fruit juice, is the range of flavors and possibilities within one region, tradition, or variety. Youthful and fresh, or aged and complex; who are we to discriminate?