The great Tom Collins Hoax Of 1874 is a joke that would not go over well today.

“Hey, so I don’t know if you know, but there’s this dude named Tom Collins who’s going around talking serious smack about you.”

“What?! Do I know a Tom Collins?” your friend mutters as she scrolls through recent Facebook friend requests. “Hold on, I think he’s that guy from the bar last week—you know, the one with the scrawny man-bun who had all those breakfast pictures on his Instagram?”

To be sure, the Great Tom Collins Hoax of 1874 would have lasted about thirty seconds in the Googling orgy that is the social media age. (And at least one silver lining to our incredibly short attention spans: a goofy joke usually has a mercifully short half-life.) But back in the late 19th Century, like many things that are protracted and un-hilarious now, it was considered a hoot. And a huge pain the ass.

The basic concept, as outlined above, is a prank. Presumably, some dastardly rapscallion in New York City thought it insanely clever to fool his friend one night, and he did so by creating a false slanderer. As the joke went, Prankster would ask Friend if he had heard of a Tom Collins. Upon removing his pince-nez and replying “Why, sir, no” (or however people talked back then), Prankster would stifle a (manly) giggle and reply that his friend should soon make the acquaintance of this Tom Collins, as a gentleman of that very name was said to be bandying about town from bar to bar, talking late 19th Century smack about him.

If the prank was well-delivered—and since back in the day, issues of slander were resolved with fisticuffs, not Tweets—the Friend would storm out into the streets of the city in search of this Tom Collins. And yes, to quote the great Rainier Wolfcastle, that’s the joke.

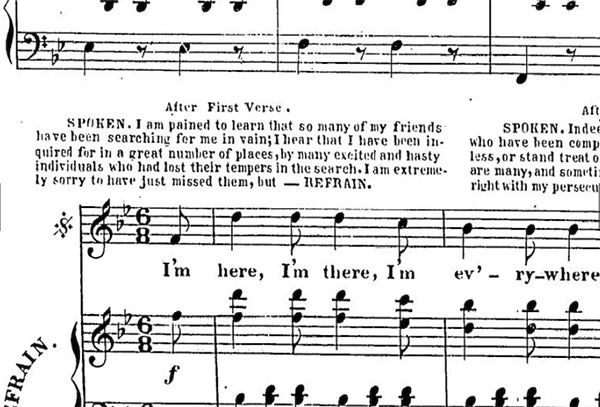

It might pale in comparison to today’s comedy standards—are we doing sarcasm again or is it irony these days?—but back in the day, the joke absolutely killed. Not literally, we hope, unless somebody took it way too far. But in New York City and Philadelphia, the joke was such a success that there were actual songs written about it, now on file in the Library of Congress. Philadelphia’s own W. H. Boner & Co. (we did not make that name up) published a song in 1874 called “Tom Collins is My Name.” “Some wretches without heart or soul/are fooling you and me.”

If you’re a fan of gin, or if you’ve seen Meet the Parents, you’ll know there’s also a drink named after this bizarro hoax.

In what must be described as a genius move of opportunistic marketing, a city bartender took advantage of the hoax by creating a drink with the same name. That way, whenever some red-cheeked gentleman came into the bar waving his cane and demanding to know if he could find Tom Collins there, the bartender could reply yes, prepare the drink, and presumably charge for it. The drink appeared in the second edition of Jerry Thomas’s “How to Mix Drinks,” which was published in 1876, so while we don’t know exactly who invented the Tom Collins drink, we know it came quick enough on the heels of the prank to pinpoint the inspiration.

So what’s in a Tom Collins? It’s actually a simple and refreshing way to enjoy gin, something a G&T lover might flirt with as a summer alternative, or a last resort when the tonic runs out. Simply London dry gin, lemon juice, sugar, and soda. Refreshing, slightly bitter, bright. Nothing to indicate the aggravation of its origins—like if a smoothie was named after that old “orange you glad I didn’t say banana” line. Just give me the drink, and be quiet. And don’t ever use Tom Collins mix.