The most popular wine in colonial America, with all due respect to Thomas Jefferson’s French favorites, was Madeira. Never heard of it? While it’s not very popular today, this fortified Portuguese wine was wildly popular on board the European ships traveling across oceans, and among the citizens of their distant colonies. Madeira was popular for a very practical reason — it travels well.

Fortifying the wine with spirits raised the alcohol content to around 19 – 21 percent, allowing the beverage to survive long journeys at sea. Two other things happened to Madeira, while at sea, that actually improved the beverage. Most wine will ‘cook’ if exposed to heat for a prolonged period of time. The hold of an eighteenth-century ship was not a kind place for table wine. Madeira, on the other hand, as sailors soon discovered, improved with exposure to heat (similar to when the Roman armies realized that storing their wine in oak barrels improved the wine within). Additionally, sailors realized that the ‘pitching and rolling’ the wine experienced in the ships hold improved Madeira’s flavor.

Madeira’s rise was also aided by the fact that the island, for which the wine bears its name, was a popular port of call for European ships headed to Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Among other supplies, a ship docking in the post would pack its hold with Madeira before sailing on to its ultimate destination.

The Americans, colonists then citizens, while they loved their whiskey, as the Whiskey Rebellion illustrated, also loved Madeira. It wasn’t the cheapest drink, but there was plenty of it in America in the late eighteen century. Historians estimate that we were importing 25 percent of all the Madeira the Portuguese were producing during the period. When it came time for an important toast in early America, Madeira was typically the drink of choice.

Toasting The Declaration Of Independence

When the members of the Continental Congress signed the Declaration of Independence in July of 1776, all the men there knew the seriousness of their action. They had signed their names to a document that would serve as the foundation of a new nation, or the evidence the British would cite when they hung them for treason. Clearly, a drink was called for. On such a momentous occasion, only Madeira would do. From there, Madeira served as the toasting beverage of choice.

Toasting George Washington’s First Inauguration

On April 30, 1789, George Washington was sworn in as the first President of the United States of America, in New York, the nation’s capital at the time. Washington, followed by a crowd of citizens, walked from his home to Federal Hall, both located in what is today Downtown Manhattan. After meeting with the House and the Senate, Washington moved to the second floor balcony, where he took the presidential oath of office.

The Madeira-soaked celebration that followed has become a bit of a legend. While all agree the inauguration was celebrated with glasses of Madiera, when that happened is a bit foggy. Some claim he took the oath with a glass of Madeira in his spare hand — most certainly not the case, while others recall a toast immediately following the ceremony. The actual Inaugural Ball was held a week later, where it was Washington’s dancing that caused a bit of a stir in early American society. Whatever the case, we can be sure Madeira was consumed, as Washington was known to enjoy three to five glasses an evening.

Toasting The Louisiana Purchase

President Thomas Jefferson was America’s earliest and strongest advocate for wine of the unfortified sort. During his time and travels in France, where he developed a strong taste for French wine, from some of today’s most famous chateaus in Bordeaux in particular, he also believed that America one day could and would produce wines to rival the Old World’s greats. His experimental vineyards in Monticello weren’t particularly successful, but his prediction proved correct. Today, America produces some of the world’s finest wines. Further, many believe those coming out of his native Virginia will soon be recognized as some of America’s finest wines (see our guides to the vineyards of Monticello and Northern Virginia).

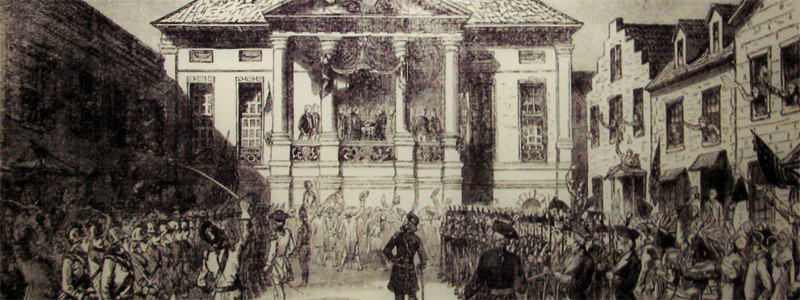

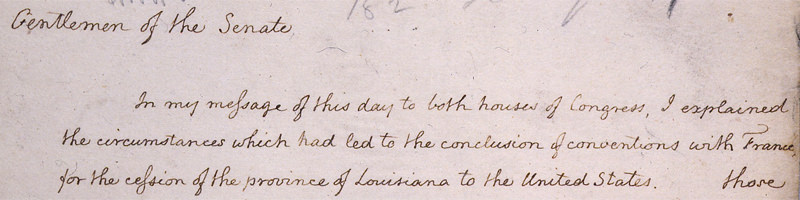

At its time, the Louisiana Purchase, was quite controversial. Many wondered whether then-President Jefferson’s decision to buy the 828,000 square mile territory from the French was unconstitutional. Jefferson himself had his doubts, but he believed the opportunity was too important to pass up. The deal itself was fairly complicated, as the French had only recently bought the territory back from the Spanish. Robert Livingston, James Monroe, and Barbé Marbois signed the treaty in Paris, in April of 1803. Later that year, following Senate ratification, the three nations marked the peaceful handover of the territory in New Orleans, its former capital, with a series of celebratory toasts: Champagne to honor France; Malaga (a fortified Spanish wine) to honor Spain; and Madeira, our adopted wine, to honor America.

…

Madeira eventually declined in popularity, becoming something of a niche beverage. This was due to a combination of reasons, ranging from the arrival of powdery mildew and then phylloxera from Continental Europe, to events abroad. America was still an important market for Madeira by the time of Prohibition, and so when Prohibition was enacted, it effects were devastating.

The American love affair with Madeira is long over. We’ve grown our own wines to replace our original ‘de defacto national wine.’ Toasting to the 4th of July with a glass of American wine would certainly be in spirit of the day, whether it’s a Cabernet Sauvignon from California or a Cabernet Franc grown across the continent on Long Island’s North Fork. But if you truly want to toast to our Independence as our Founding Fathers would have, Madeira should fill your glass.