In July 2008, the Seattle microbrewery Elysian made a special beer for the 20th anniversary of Sub Pop Records, the influential local record label that had launched the careers of Nirvana and Soundgarden. The pale ale was called Loser, a sarcastic term of endearment at Sub Pop, whose higher-ups were more interested in artistic integrity than the bottom line. So, too, would this beer follow that ethos — the label offered up the slogan “Corporate beer still sucks.” Seven years later, Elysian would be acquired by the largest beer corporation in the world, Anheuser-Busch InBev (ABI). Now it was corporate beer and, to many in the craft beer industry, its beer suddenly sucked.

“I always liked it when my favorite band signed with a bigger label,” claimed co-founder Joe Bisacca. “I wouldn’t stop buying their records.”

But many did.

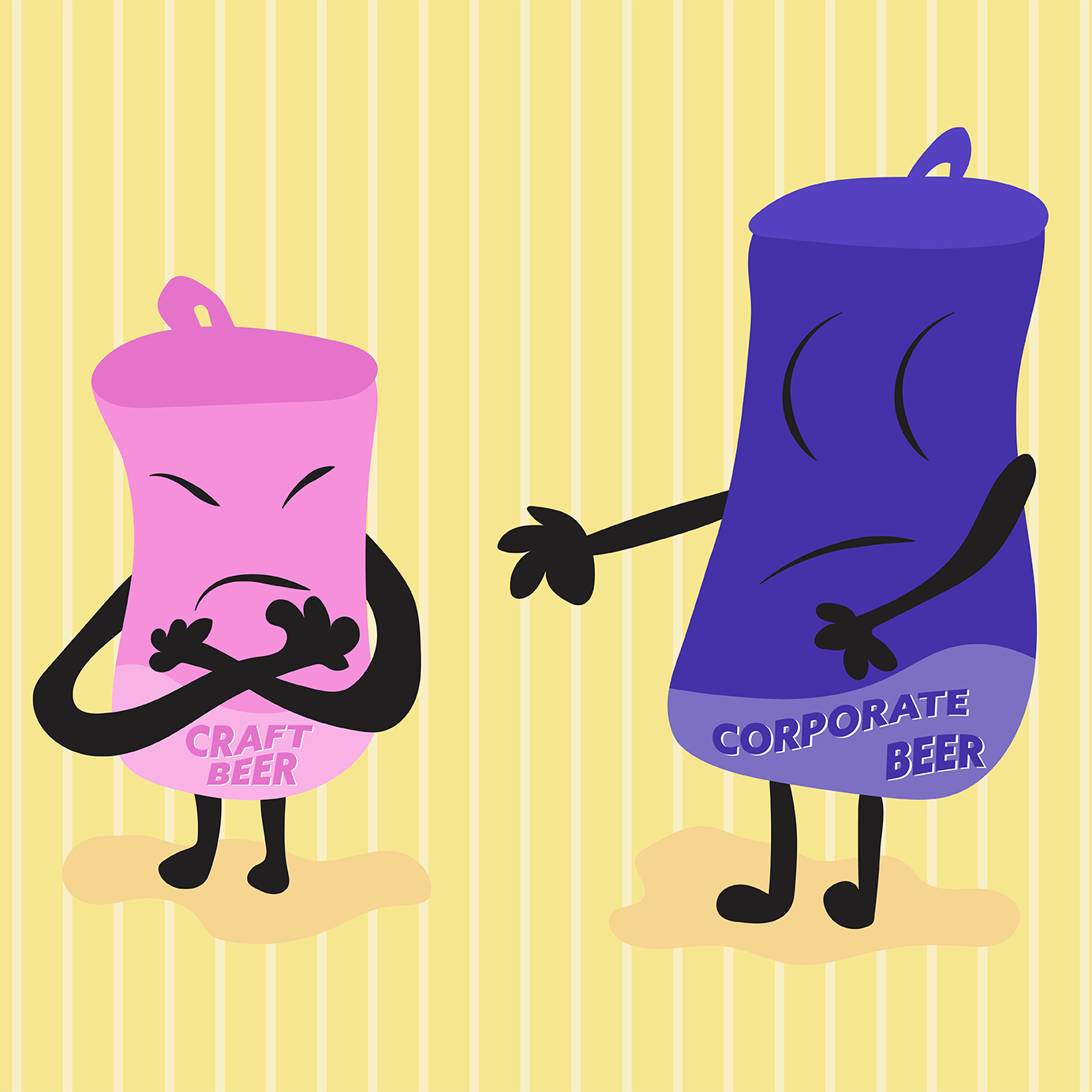

That’s because the modern craft beer revolution was founded on an “us-against-them” mentality. Right from the early days of Sierra and Sam, there were two sides: “us,” the people who made and drank small, mom-’n’-pop-owned, flavorful craft beer; and “them,” the massive, soulless, international companies that made factory-cranked-out swill.

The dichotomy worked for a good decade or two. If you were drinking “good” beer it was from and for “us”; and if you were drinking “bad” beer it was, generally, from “them.”

Today, however, it’s become increasingly difficult to determine who is an “us” and who is a “them.” So, O.K., ABI and its so-called High End of craft breweries it has acquired (like Elysian) are clearly a “them.” Then why do beer geeks still line up every Black Friday to purchase the ABI-owned Goose Island’s Bourbon County Brand Stout?

What about the craft breweries owned by giant corporations that just aren’t as giant as ABI? Lagunitas, for example, is now owned by the world’s second-biggest beer company, Heineken International. Is it one of “them”?

Then there are craft breweries only partially owned by bland international conglomerates, like Founders and its 30 percent stakeholder, Mahou-San Miguel. Or Brooklyn Brewery and its 24.5 percent stakeholder, Kirin Holdings, not to mention its international investment and distribution partners, Carlsberg Group.

There are breweries built or now owned by private equity, like Cigar City and Oskar Blues. Are those a “them”? What about if you’re owned by one rich dude who doesn’t even like IPAs and is just cynically trying to make a profit? “Them”?

There are also breweries owned by a semi-large international beer company that people actually respect, like Duvel Moortgat, which counts Firestone Walker, Boulevard, and Ommegang in its portfolio. I’ve never seen any of those excellent breweries labeled as a “them.” But, like, what’s the difference, really?

It’s all in the eye of the beholder. And it’s causing a rift that is tearing apart the industry. This is a golden age of infighting among brewers, among fans, and among the beer media. It risks harming the entire beer industry with all its finger-pointing.

Consider Beavertown Brewery, a cult North London craft brewery owned by a Led Zeppelin rocker’s kid (how cool is that?!), who himself had long shit on corporate beer. Nevertheless, in June, Beavertown sold a £40 million minority stake to Heineken International.

The problem was, its annual beer festival, the Beavertown Extravaganza, was just 11 weeks away and featured plenty of other “us” breweries. It didn’t matter if Logan Plant claimed Beavertown was still independent. Almost immediately, another cult U.K. brewery, Cloudwater, withdrew from the Extravaganza in the loudest way possible: an “us” versus “them” blog post.

“[O]ur decision to withdraw is based at its core on us standing up for independence, and standing against disturbing corporate tactics employed by big beer that should never have any place in craft beer,” the brewery wrote before offering a laundry list of craft beer-ruining charges against Heineken.

The exact same thing had happened a year earlier. In May 2017, Wicked Weed was acquired by ABI. Its annual Funkatorium Invitational was set for July, but it had to be canceled after 51 of the 74 invited breweries pulled out of the event, including such big names as The Rare Barrel and Jester King.

Why, there’s that esprit de corp the industry was built on!

The funny thing is, when you dig deeper into Wicked Weed’s history, you learn that, even when everyone considered them an “us,” they were still a bunch of rich dudes. This wasn’t a secret — we, us, perhaps just chose to ignore it.

Co-founder Walt Dickinson was a serial entrepreneur who had made bank with a rainwater reclamation company, Higher Ground; his financial partners, family friends Rick and Denise Guthy, created a multi-billion-dollar company selling infomercial products like motivational tapes and Proactiv skincare. It was no coincidence that on the day they opened in 2012 they already had a two-story, 7,000-square-foot brewpub with 17 house taps, able to accommodate 500 customers.

“Some locals thought it was so slick it must be part of a chain,” wrote Capital at Play, an investment magazine. (That was praise.) “Others conjectured that it might have been bankrolled by investors from Charlotte or Atlanta who wanted to cash in on the Asheville beer scene.”

Upon Wicked Weed’s acquisition announcement, Scottish brewery BrewDog immediately canceled the Asheville label’s upcoming tap takeover at a few U.K. pub locations. BrewDog likewise pulled out of the Beavertown Extravaganza with a look-at-us blog post.

If there’s any brewery that has tried its damndest to be an “us” brewery, it’s this Scottish firebrand. The company claims it launched because its founders were “bored of the industrially brewed lagers and stuffy ales that dominated the U.K. beer market.” In 2011, the company offered “Equity for Punk” (i.e. crowdfunding shares) totaling £2 million, the equivalent of 8 percent of the capital of the company. Last year it sold $7 million more to help launch an American location.

Of course, while BrewDog is not owned by any sort of dreaded international conglomerate, it is a multinational brewery (with over 50 locations in places such as Barcelona, Rome, Sao Paulo, and even Columbus, Ohio) that now has nearly a quarter of its ownership locked up in the private equity dollars of TSG Consumer Partners. TSG ponied up approximately £213 million in April 2017; not a big deal for them, as they also have major investments in such punk companies as Planet Fitness, Famous Amos, Vitamin Water, and Pabst Blue Ribbon.

So… is BrewDog one of “us” or “them”? Maybe if BrewDog throws a beer festival, 22 percent of the craft breweries should pull out?

Some argue private equity dollars are preferable to a big brewery acquisition — after all, these suits in New York neither own a full share nor care about having any sort of creative control. Ah, yes, but they do care about making money quickly. Thus, on the other side of the private equity issue there’s Beavertown founder Logan Plant. You know, the guy who just sold out to Heineken. In the same “us” versus “them” blog post he wrote:

“Private Equity groups offered the cash but across the board Private Equity seemed to be driven by maximising return on investment ASAP. Investors from these financial houses are not in it for the long run, or for the love of the product or industry they are investing in. They don’t care for the nuances and delicacies of your business. They want money in and money out x 3 as fast as possible. (sic)”

He’s got a point.

Another craft (or not craft! your call!) brewery that TSG has invested in is SweetWater Brewing. It’s instructive to look at this Atlanta brewery compared to another craft brewery from the region, Creature Comforts. Even if your average beer-drinking Georgian doesn’t know about the TSG involvement, most no longer regard SweetWater as the paradigm of an “us” brewery these days.

Opened in 1997, SweetWater is now the 16th-largest craft brewery in the country. It’s served at the ballpark, Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, and on Delta flights. Meanwhile, the tiny Creature Comforts — an Athens operation so small a pet therapy company comes up first if you Google its name —has become ballyhooed across the nation for its IPAs and barrel-aged sours. According to Beer Advocate users, Creature Comforts currently produces six of the the 10 best beers in all of Georgia.

But here’s the thing: Creature Comforts was founded by a former finance guy from Diageo, Chris Herron. Diageo is, of course, the world’s biggest beverage company. It uniquely understands how big beer, how big alcohol work, and is always trying to blur the line between “us” and “them.” Right after the Wicked Weed acquisition, Herron penned a Good Beer Hunting piece called “Watch the Hands, Not the Cards — The Magic of Megabrew,” writing:

“While everyone thinks that AB InBev is truly interested in getting into craft and building these brands (which is a secondary goal at best), I submit that maybe buying craft breweries is more of a tool to devalue the craft category and increase the brand equity of their core legacy beers [in other words, Bud Light].”

Maybe that’s true, maybe it isn’t, but, I’m guessing, as long as you continue thinking Creature Comforts is with “us,” not “them,” Herron will be happy. Well, at least until he, too, wants to grow a bit and decides to redefine things.

Of course, the official say regarding who is an “us” and who is a “them” brewery and who we should heap our scorn on comes from the Brewers Association. In fact, I’d argue the BA is the most divisive player of any one currently in the industry. This trade group, and this trade group only, has the ability to transform breweries from craft to not craft overnight. And it continues to move the goalposts every year depending on who it wants to include — and now exclude. Or, better put, whose money it is willing to accept and whose it isn’t.

The biggest “us” brewery in America according to the BA? Yuengling, which no one on planet Earth actually considers a craft brewery. Do you know many craft breweries that sell $9.99 12-packs of light beer? But because Yuengling is independent and 100 percent owned by Dick Yuengling, the BA calls it craft. In early 2018, the BA started making “independent” the most important part of its craft definition, encouraging breweries to add a special independent seal to their bottles and cans.

On the BA’s list of the country’s largest craft breweries also sits the entire Duvel Moortgat troika, in fourth place. And, O.K., I agree Firestone Walker, Boulevard, and Ommegang are craft, but how can they be considered “independent” when Duvel Moortgat owns them?

Likewise, Kirin’s previously mentioned 24.5 percent stake in Brooklyn Brewery isn’t some random figure. According to the BA, a brewery is still “independent” if “less than 25 percent of the craft brewery is owned or controlled (or equivalent economic interest) by a beverage alcohol industry member which is not itself a craft brewer.” Thus, Brooklyn currently sits as the BA’s 11th-biggest craft brewery. Never mind that Brooklyn Brewery itself is on the road to being a conglomerate, partially acquiring 21st Amendment Brewery and Funkwerks in 2017. (Are those two breweries now a “them,” owned by an “us,” partially owned by a “them”?)

Does any of this make sense? And, more importantly, is all this silliness actually helping the industry?

This small-versus-big, indie-versus-corporate, us-versus-them side-taking exists in just about every creative field, yet it doesn’t seem to result in nearly as much annoying, buzz-killing, business-bankrupting infighting.

Dave Eggers went from a hip, San Fran novelist to a publishing magnate. David Chang from owning a small noodle shop to a restaurant empire. Michael Kors from a small luxury brand to a rapidly expanded fashion house. They’ve all had mixed success and certainly muddied their legacies, but no one small feels threatened by their mere existence.

This even extends to other alcoholic beverages. When is the last time you heard your small, local whiskey distillery griping about Beam Suntory? Or that hip pét-nat producer bitching about Gallo? They mostly aren’t, which is perhaps one key reason that both spirits and wine are stealing more market share from craft beer than big beer actually is.

I thought this was best lampooned by the Good Beer Hunting twitter account, which tweeted a video of a snake fighting a cat while simultaneously being eaten by a frog and simply captioned it: “Craft fighting macro while wine + sprits eats market share. (sic)”

As I was finishing this piece I got an email from the Brewers Association offering its mid-year statistics for craft breweries. Industry growth is still happening, though only at a 5 percent clip. More breweries are opening today than ever before, but more are closing, too — reportedly some 165 in the last year alone.

One of the breweries that just closed is Green Flash. Previously one of the hottest names in craft beer because of its iconic West Coast IPA, the bigger the brewery became, the less cool it was seen by “us.” Revenue had been trending downward, and the brewery claimed it had taken on too much debt, expanding to the East Coast with a lavish $20 million, 58,000-square-foot location in Virginia Beach. A few days later it closed a barrel-aging facility in Poway, Calif., and pulled its beer distribution from 42 states.

This isn’t a singular sob story. Big names like Smuttynose Brewing Co. and Speakeasy Ales & Lagers also (briefly) went out of business this year.

A reprieve came in April 2017 when Green Flash was sold to an ownership group cheekily called WC IPA LLC. Meanwhile, Smuttynose was auctioned off to another private equity group, and Speakeasy was bought by the former owner of a beer distributor who quickly put a former ABI consultant in charge.

I guess if you literally can’t keep existing as an “us,” you might as well finally become a “them.”