Wine nerds are often also soil nerds. Soil directly and indisputably affects the wine that is produced in a given region. In addition to climate and aspect, soil is part of what makes a region’s terroir and can separate mediocre winemaking areas from superior ones.

The Dirty Guide to Wine, a newly published book by award-winning journalist and author Alice Feiring with Pascaline Lepeltier, MS, explores the complexities of soil and its impact on wine. It’s an important read for anyone passionate or curious about wine and terroir. Having recently read the book, I was inspired to learn more about soil and share that with VinePair readers.

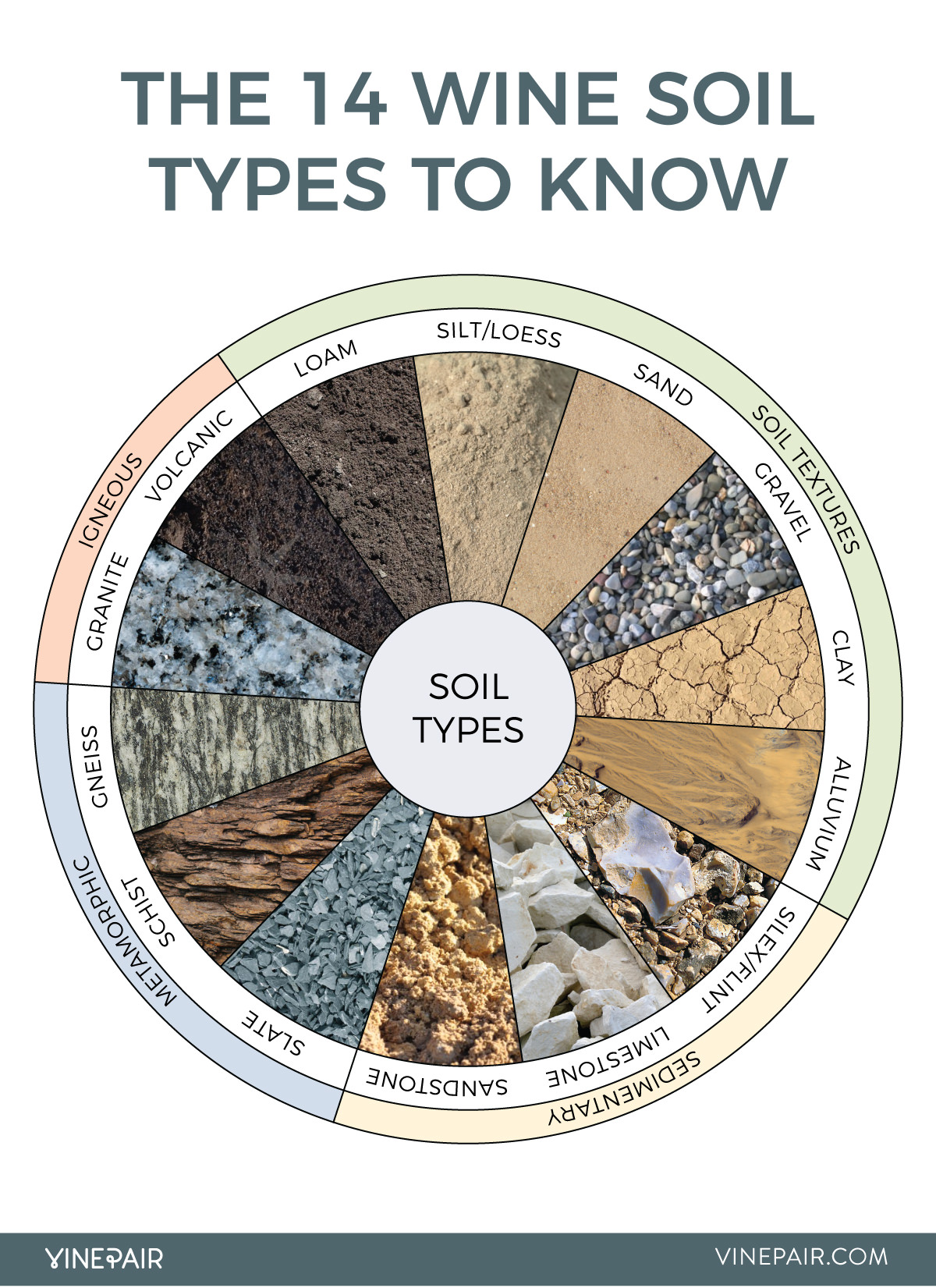

Breaking soil down into singular categories is quite difficult. Most vineyard topsoils are not homogenous; rather, they are often a blend of different soils, and both the rocks within and the texture of the topsoil influence a region’s wines. The concept of minerality — that is, the perceived aroma and flavor of a soil in the wine itself — is another factor. But, in terms of the actual successful growth of a grapevine, some soils work better than others.

While certain soil characteristics are suited to different regions, generally vineyard soils should not be too fertile. This may seem counterintuitive, but soils with fewer nutrients force vines to struggle and therefore become stronger. Water is also essential to grapevines, so good wine soils should retain water while still draining it away from the surface.

For those of us without a geology degree, VinePair created a helpful illustrated guide for an overview of the many soil types worldwide.

Igneous Soils

Igneous soils can be either intrusive or extrusive, made from the cooling and solidification of magma or lava from within or without the Earth’s crust.

Volcanic

Volcanic soil, particularly basalt, is an extrusive soil formed from cooled, hardened, and weathered lava. While the soil is a complicated one, it tends to be finely grained, drains well, retains and reflects heat, and holds water. Volcanic soil also contains high proportions of iron, resulting in black- or red-colored earth, and is thought to sometimes impart an ashy, rusty taste to wines.

Famous regions: Sicily, Canary Islands

Granite

Formed under the Earth’s crust by slowly cooling magma mixed with quartz, granite is found in a range of soils and textures throughout the world. Its elevated pH promotes high acidity, and the rock is porous enough to create deep-rooted vines, producing layered, subtle, blossoming aromas and flavors that can develop for years.

Famous regions: Cornas, Rías Baixas

Metamorphic Soils

Metamorphic soils have been transformed from another type of rock through heat and pressure over millions of years.

Slate

Closely related to but less compressed than schist, slate is an alluvial deposit formed under heat and pressure. Dark and variable in color, slate is easily broken but not as subject to weathering as other soils. It both absorbs and reflects heat, helping to ripen grapes.

Famous region: Mosel

Schist

A hard, crystalline rock more dense than slate, schist is made of layers of minerals that can flake off easily. It retains heat well, producing big, powerful wines with rich minerality.

Famous regions: Douro Valley, Ribeira Sacra

Gneiss

Gneiss is a fairly infertile soil formed from either volcanic, granite, or schist soil that looks similar to granite. Minerals are arranged in bands that run through the rock, but it is a very hard, infertile soil, making it good for grape-growing.

Famous regions: Wachau, Kamptal

Sedimentary Soils

Sedimentary soil is comprised of solidified mineral or organic deposits from the Earth, often left by bodies of water.

Limestone

Some exalt limestone as the finest wine-producing soil in the world and, indeed, it is found in many famous regions. It forms from the decomposed bodies of mollusks, fish, and other organic material that once lived in ancient seabeds and reefs. Limestone and chalk (a type of limestone), drain well but also hold water for vines to absorb when needed. Wines made in limestone soils are generally long-lived and have bright, linear acidity.

Famous regions: Burgundy, Champagne, Jerez

Sandstone

Sandstone is comprised of sedimentary rock, sand-sized particles that have been compacted together over time by pressure. Depending on what rocks the sandstone is made of, it can come in various colors, but it commonly contains quartz and feldspar.

Featured regions: Chianti Classico (locally called alberese)

Silex/Flint

The hard, metal-like silex, which contains a high proportion of flint, is made from silicon dioxide. It stores and reflects heat well, providing ripeness in regions that might otherwise be too cold for grape growing. It is often credited with giving wines a rich, flinty minerality.

Famous regions: Sancerre, Pouilly-Fumé

Soil Textures

Many wine soils are defined by their textures, which are comprised of types of igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic rocks.

Sand

Sand is any rock that has been pulverized into small particles. Because sand drains easily it works well in wet climates; but for drought-riddled regions, sandy soil can be problematic. It is, however, often phylloxera-free since the pest can’t survive its texture. Sandy soils can sometimes result in thin, uninteresting wines, but in the best areas they produce wines with delicacy and drinkability.

Famous regions: Barolo areas of Serralunga d’Alba, Monforte d’Alba, and Castiglione Falletto

Clay

A topsoil of clay expands and contracts with water, but deep clay subsoil retains precipitation and minerals, and can be a savior to grapevines in dry times. Some say that clay imparts a profile to wines that is similar to the texture of clay itself — thick, round, and generous.

Famous region: Pomerol

Gravel

The texture of gravel can range from the size of a pebble to the size of a fist. It is most helpful in absorbing heat and reflecting it onto grape varieties, particularly at night when temperatures tend to cool. This allows a region to make wines that are bigger and more alcoholic than they typically would be in that climate

Famous regions: Left Bank Bordeaux, Cháteauneuf-du-Pape

Silt/Loess

Silt is a soil more finely textured than sand. It retains more water, which can sometimes result in overly compacted and waterlogged growing conditions. While some silt soils can be too fertile for quality wine production, one good variety is loess, a type of wind-blown silt comprised mainly of silica.

Famous regions: Niederösterreich (Lower Austria), primarily for Grüner Veltliner

Loam

A warm, soft, crumbly mix of sand, silt, and clay, loam can sometimes be too fertile for quality winemaking. But when blended with other soils in the right amounts, it can make powerful, voluptuous wines.

Famous regions: Barossa Valley

Alluvium

Alluvial soil is a blend of soils, comprised of a combination of clay, silt, sand, and gravel. This combination, called alluvium, is deposited over many years by running water. Alluvial soil typically contains a lot of organic material, making it quite fertile, but is present in many of the world’s wine regions.

Famous regions: Napa Valley floor regions (Rutherford, Yountville)