In the late 1970s, owners of mom-and-pop shops in Chicago were calling the Chicago Sun-Times with complaints about city officials demanding payoffs for business licences. None of the callers wanted to go on the record, though, for fear of retribution.

To get to the bottom of the story, the reporters needed proof. They needed to catch the crooks red-handed. So the newspaper bought a bar.

In 1977 Pam Zekman, a Sun-Times reporter, and Bill Recktenwald, a Better Government Association (BGA) investigator, posed as a young married couple opening a tavern in downtown Chicago. Zay N. Smith, another Sun-Times reporter, served as a bartender. Photographer Jim Frost donned coveralls and hid his camera in a toolbox to pass as a repairman.

By pretending to be community members, the team hoped to expose the web of corruption shaking down small and independently owned businesses throughout the city.

And in Chicago, this is no small task. For many locals, city politics are synonymous with graft, extortion, and fraud. Just last winter, the Chicago Tribune called the city “the political corruption capital of the United States.”

At that time, an elected assemblyman was indicted for federal corruption. He was the city’s third alderman indicted while in office — his predecessor was incarcerated — and the 30th Chicago alderman convicted of crimes related to their positions since 1972. On a state level, four of the last seven Illinois governors have gone to prison.

‘When we were a reporter and an investigator, people wouldn’t talk. Now that we were a husband and wife pretending to buy a tavern, people wouldn’t shut up.’

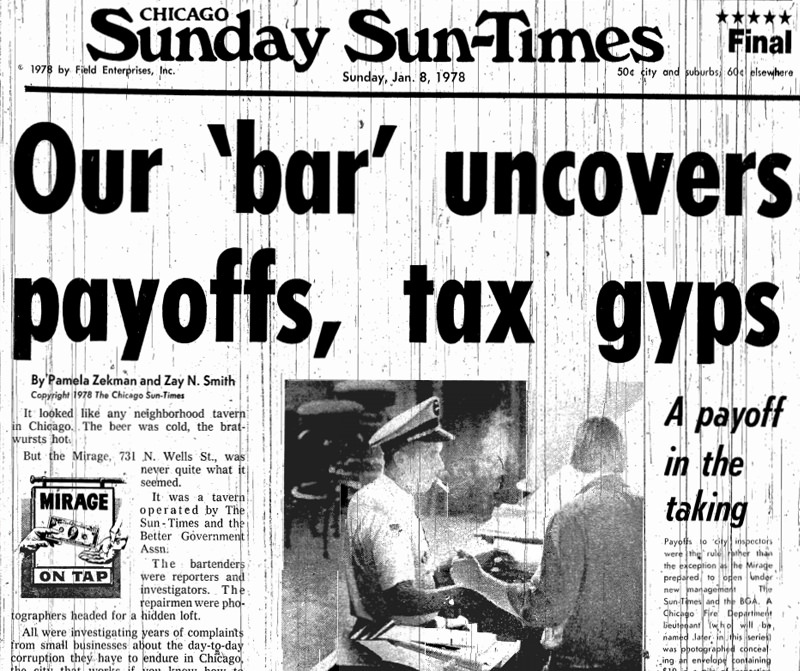

In January 1977, the Sun-Times and BGA pooled resources to purchase a nondescript tavern at 731 North Wells Street. Zekman and Recktenwald posed as aspiring bar owners Pam and Ray Patterson. They paid $5,000 down on the building’s $18,000 asking price. (The total cost of this project for BGA and the Sun-Times was $25,000.)

The network of corruption was immediately apparent. Unscrupulous building and fire inspectors were so flagrant that the person who brokered the “Pattersons’” real estate deal offered insights on the cash amounts they should expect to pay each inspector.

Other small business owners also shared tips on who to bribe, how, and for how much. All were unprompted.

“We had interesting conversations with people who were owners [of neighborhood businesses] about, ‘Yeah, you had to pay people off.’ Very frank discussions,” Recktenwald says in Topic’s fantastic oral history of the project. “When we were a reporter and an investigator, people wouldn’t talk. Now that we were a husband and wife pretending to buy a tavern, people wouldn’t shut up.”

They called their fake bar The Mirage. (Get it?)

The Mirage opened in July 1977. It had a pinball machine, Marimekko textiles, and a basement filled with maggots that the team paid an inspector to ignore. The bathroom was not up to code, and the pipes leaked.

“I think one of the things that amazed us is that these inspectors sold out public safety on the cheap,” Zekman said. “They were not taking huge amounts. We were told to leave $10 for one inspector, and $25 for another.”

The Mirage was a fake bar, but the reporters really had to run it. Zekman recalls being asked to make a Margarita and having no idea how to rim a glass with salt. Smith enrolled in bartending school.

“It was a good bartending school; I learned how to make 85 drinks,” Smith says.

Even the worst bar attracts flies. Throughout the sting operation, The Mirage garnered a few loyal customers. The reporters were terrified of being found out.

“One of our customers who came in every day, suddenly said to no one in particular, but loudly, ‘I’ve figured it out, this place is a front!’” Smith says. “I just laughed him off.”

By pretending to be community members, the team exposed the web of corruption shaking down small and independently owned Chicago businesses.

In October 1977, four months after opening, The Mirage closed. The Chicago Sun-Times launched a 25-part, wildly successful series covering the investigation in January 1978. Its efforts exposed systemic tax fraud that had cost Chicago $16 million a year, and the Illinois Department of Revenue launched a subsequent tax fraud force, the “Mirage Unit.” Nearly 20 corrupt city officials were fired.

Because the project relied entirely on undercover reporting, it was controversial in some journalism circles, particularly the Pulitzer committee, which did not award the Sun-Times’s work.

There are intricacies to journalistic ethics. While debates regarding fake news may seem utterly of-the-moment, that’s totally a mirage.