Dave Kyrejko loves beer. He also loves whiskey and science. And that’s where the monster comes in.

“Yep, it’s the two-headed monster,” Kyrejko tells me. “That’s the official name.” We’re standing inside Interboro Spirits and Ales, an airy warehouse-turned-craft-brewery in an industrial stretch of East Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Arcane Distilling, Kyrejko’s micro-distilling venture, has been operating out of the space since June 2017, and at the heart of it is the monster: a towering, two-tiered vacuum still made up of bubbling glass orbs, coils, tubes, and metal odds and ends. It’s basically the coolest chemistry set you’ve ever seen. Why? Because it turns delicious craft beer into equally delicious craft whiskey.

Kyrejko is an engineer by training, and Arcane’s line of beer whiskeys, known as Lone Wolf, represents the coming together of his three major passions: beer, whiskey, and science. It’s kind of like a boozy trifecta.

“I’ve been in the alcohol industry for seven years at this point, building stills and stuff like that, but this is my first solo venture,” he says. “I basically built it around the idea of beer whiskey, very specifically, vacuum-distilled beer whiskey.”

If you know anything about distilling whiskey, you probably know that all whiskey, essentially, begins its life as beer. But 99.9999 percent of the time, that beer isn’t made to be consumed on its own. It’s a quick and dirty collection of chemicals solely intended to kick off the alcohol production through primary fermentation. Later, of course, that yeasty, fermented liquid, often called distiller’s beer or “the wash,” gets dumped into a still and boiled, its alcohol-rich vapors are extracted and cooled, and then, badda bing, badda boom, you’ve got a distillate ready for barreling.

But whereas traditional whiskey distillers generally don’t invest in that initial beer stage — they don’t hop it or add any additional flavors; they don’t let it ferment as long as a brewer would — Kyrejko does just the opposite. Rather than attempt to remove some of the beerier aspects, he aims to preserve them, producing a liquid more akin to the delicate, fragrant, and nuanced brew he began with, just in concentrated form.

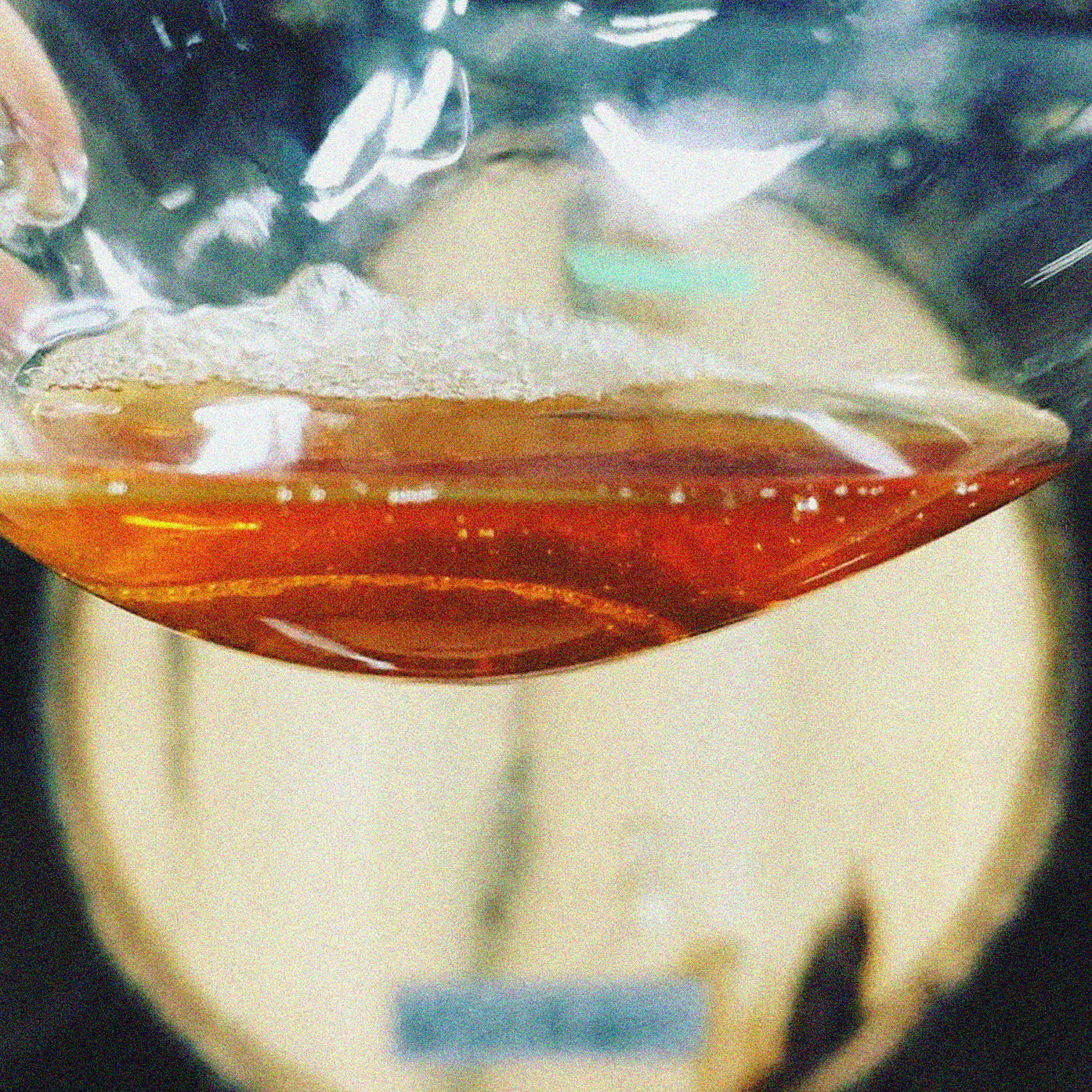

It’s no small feat. Regular stills like the copper pots and steel columns you see around the world remove all those aromatic and flavorful esters that characterize a pint-worthy beer to create a consistent, pure, and grain-forward product. That’s why Kyrejko, ever the tinkerer and hungry for a challenge, went to work on something all on his own, a machine that eschews traditional flavor-destroying heating processes by using a vacuum still that allows the liquid to boil at a much lower temperature. There’s nothing else like it (seriously, his patent is pending).

“Beer is really hard to distill because it’s so delicate,” he explains. “Somebody stores an IPA the wrong way and you fucking know it. So imagine if you were cooking that IPA instead, and then you had to drink what was left over. It’ll work — you’ll get alcohol out of it, but it won’t taste like the beer anymore. It’ll be kind of vegetal, weird. You’ve pretty much lost all of its delicate components. What my process does that’s different is that I allow the ingredients to be themselves. They’re not changed in the boiler. I’m not messing with the flavors, just collecting them.”

While there are other distilleries making whiskey from craft beer, such as Charbay Artisan Distillery & Winery and Seven Stills Distillery, both in California, Kyrejko’s unique setup allows him to extract those flavors in a more precise and layered form that doesn’t require extensive aging. A card-carrying member of New York’s homebrewing community, he was first drawn to the process’s educational possibilities.

“I was hanging out at a lot of homebrewers’, and it was almost like a teaching tool,” Kyrejko recalls. “I was wondering how to get the flavors in their beer concentrated out just to show them, like, ‘Hey, I can isolate this and that.’ That led to more and more sophisticated machines, and before you knew it — well, three years later — Arcane became a thing.”

Kyrejko knew from the start that he wanted to collaborate with New York-based breweries. He loves and respects the makers and the feeling appears to be mutual, due in large part to his undying commitment to honoring the product. And working with local breweries also allows him to educate the public about his passions.

“You’ve got this great sort of chain,” he explains “If you come to the tap room, you can actually sit down, order the beer, and try the whiskey right next to it, seeing how one is of the other in a real way. What’s great about making an imbibable product is that now I can talk about the science most people glaze right over. You’ve got this thing in your hand that you’ve never had before and we’ll say something like, ‘Well, there are esters involved.’ Distilleries don’t talk about that. Brewers do.”

Arcane announces its Lone Wolf releases, often quite limited, through Instagram. Kyrejko has released 57 batches to date, and demand continues to skyrocket. The clientele, a mix of beer people and whiskey people, provides Kyrejko ample opportunity to blow minds with the magic of science, while growing the community he knows and loves.

“We get people that show up just for the whiskey, and they wind up staying and having a bunch of beers,” he says. “For the last year, each batch was, at most, 20 bottles. They’d go in a week, even a weekend. It was interesting to see who would come out because they might not be beer drinkers. And it was also interesting that the beer drinkers that came out were almost unilaterally not whiskey drinkers. Like a sort of cross-pollination of two major worlds.”

At the end of the day, Kyrejko is a brewer in a distiller’s world. It might sound unorthodox, but it’s actually a natural fit.

Like science, American craft brewing has always been based on the principle of experimentation, of trial and error. The movement’s pioneers weren’t just trying to replicate century-old European recipes, they were dead-set on doing their own thing. That creative, individualistic ethos helped build a culture based not on perfectionism and preciousness, but on comradery and curiosity.

“Beer people are great people. What’s there not to like?” he asks. “I’ve never met a brewer that isn’t happy to discuss their process. And if something goes wrong, they’ll talk about that, too. It’s not really like that with spirits. It’s more, ‘You just insulted my child.’”

In that, Kyrejko’s business is about so much more than making great whiskey. It’s about bringing people together, every step of the way.

“I don’t think you’ll ever find Lone Wolf on store shelves,” he continues. “It’s not the purpose. I want you to visit that brewery, you know? I want you to sit down at that bar, order a beer, and then buy your bottle of Lone Wolf. I want you to experience it all together.”